Light & Land

Art Wolfe interview: “The challenge is to evolve.”

11th May 2019

From early expeditions to Tibet to visiting the tribes of Ethiopia, Art Wolfe has proven himself over the past 40 years as a photographer who’s prepared to go the extra mile for his photographs. Famous for his TV series and fascinating books, his work around the globe encompasses landscapes, wildlife and people, often including photos of disappearing cultures or threatened species or environments.

Here, he talks to Graeme Green about rhino attacks, finding new angles, America’s National Parks and how photography can be a force for good…

You photograph wildlife, landscapes and people. Which do you most like working on?

The minute I’m fully engaged in photographing some critter, that’s the most important thing to me. Yet when I’m walking the back streets of Havana in Cuba, finding abstract art in the decay, that’s the most important thing. It’s whatever I’m focusing on. That shows you how focused and determined and dogmatic I am. You have to be that way.

Which countries do you particularly like spending time?

I live in Seattle but I think of myself, honestly, as clichéd as it might sound, as a citizen of the planet. I feel more akin to all my friends around the world than necessarily being a Seattleite.

Anywhere where I travel, I love. The only place I ever had negative memories was Russia, oddly enough, and that was in the early 1980s when it was still a Communist country.

I’ve travelled all through Europe, China and Japan, Australia, Southeast Asia… I always look at these countries with great fondness because I’ve had great photographic opportunities. You tend to let go of any kind of hardships or inconveniences or minor mishaps. You just forget about those and remember the positives.

What was your first major adventure?

Going to the top of Kilimanjaro was one of the hardest things that I did. In November 1980 when we did that, the border between Kenya and Tanzania was closed and there was nobody in Tanzania. There were no other people on the mountain when we climbed it. There was only one porter, who wasn’t really a porter, so we carried our own gear and we climbed that son-of-a-bitch mountain in four days. That is almost impossible to do. We were young, we were fit but still I had some health issues on the summit.

Getting up the mountain was an adventure and then we went down into the Ngorongoro Crater. There was nobody down there, so we could camp in the crater back then. A bunch of lions came roaring at night all around our tent. That was a real adventure.

Over the years, you’ve often returned to the same places multiple times. What’s your approach for finding new perspectives on places you’ve already photographed?

The challenge is to constantly evolve your work and not to be so satisfied or self-anoint yourself as ‘arrived’. The success I’ve had over the years comes out of the art school where my instructors would hammer home ‘Never be so satisfied that you think you’ve done it all. Always put the carrot slightly beyond your reach, so that you’re always moving forward and evolving,’ and that’s what I’ve done.

40 years into this business, this lifestyle, this passion, I’m as enthusiastic as I was 40 years ago. I think the big death for a lot of artists is when they run out of enthusiasm, run out of ideas, run out of inspiration. So when I return to a place, the likelihood is that I’ve evolved. You’re always bringing something new to a place you’ve been to. I think that’s a great and worthy challenge.

You’ve said that you were a conservationist and environmentalist before you were a photographer. How do you see the connection between photography and conservation?

Many of my photos over the years have been the centrepiece of campaigns to preserve a habitat or animal. If you're make a living of the natural world, you have to pay back to the natural world. Even if I wasn’t into photography, I would feel compelled to do that because we all have that vested interest in keeping the Earth as healthy as we possibly can.

You’ve photographed many different cultures, from Venezuela to Papua New Guinea. What do you look for when you’re photographing people?

I’m looking for somebody who has something unique about them. It can be eye colour. Lets face it: Steve McCurry became famous over the Afghan Girl’s eyes.

I took some photographs a while back of old ladies with wrinkles, when I went to Tanzania with a monograph monochrome camera by Leica, which is all dedicated black and white, and I had the idea of finding chiseled old people with the more wrinkles the better.

I’m always looking for people who actually make me happy looking at them. They could be, for example, the strangest people that I can find at the Kumbh Mela gathering in India, like sadhus and snake charmers. I don’t want to find somebody who looks like they came straight out of Hollywood. I’m looking for personality.

Animals (and humans) are unpredictable. Have you ever had any close calls?

I have, and these times are badges of stupidity, rather than honour. I once nearly got killed, as did my assistant and two guides in Nepal. I was working on a book called The Living Wild, which Richard Dawkins out of Oxford wrote for. I went in to Nepal to try to find and photograph the world’s largest subspecies of rhino. Little did I know that these rhinos were extraordinary aggressive towards humans. They had previously been hunted by the King of Nepal in this very park, so they equated humans to danger. The only way of defence for a rhino was to attack. I, of course, knew none of this while I was walking in the forest looking for these ‘silly critters’.

When I found one, it immediately attacked, pinning myself, my assistant and the two guides down between the roots of one tree and it was goring at us. The roots of the banyan tree, which are above the ground, became a barrier to stop the rhino closing that last two feet to get to us. Had it not been that type of tree, it would’ve nailed us and killed us. They’re eight and a half feet tall at the shoulder and they’re very imposing, very aggressive beasts.

The rhino would have won that fight?

Not only won. It would’ve pulverised us.

Are you always on the move?

I’m not a really good sitter-arounder on a beach. I love either working in my own garden here in Seattle or travelling, or working, or lecturing, passing on whatever I’ve accrued. I’m that classic ‘Type A’ type.

-

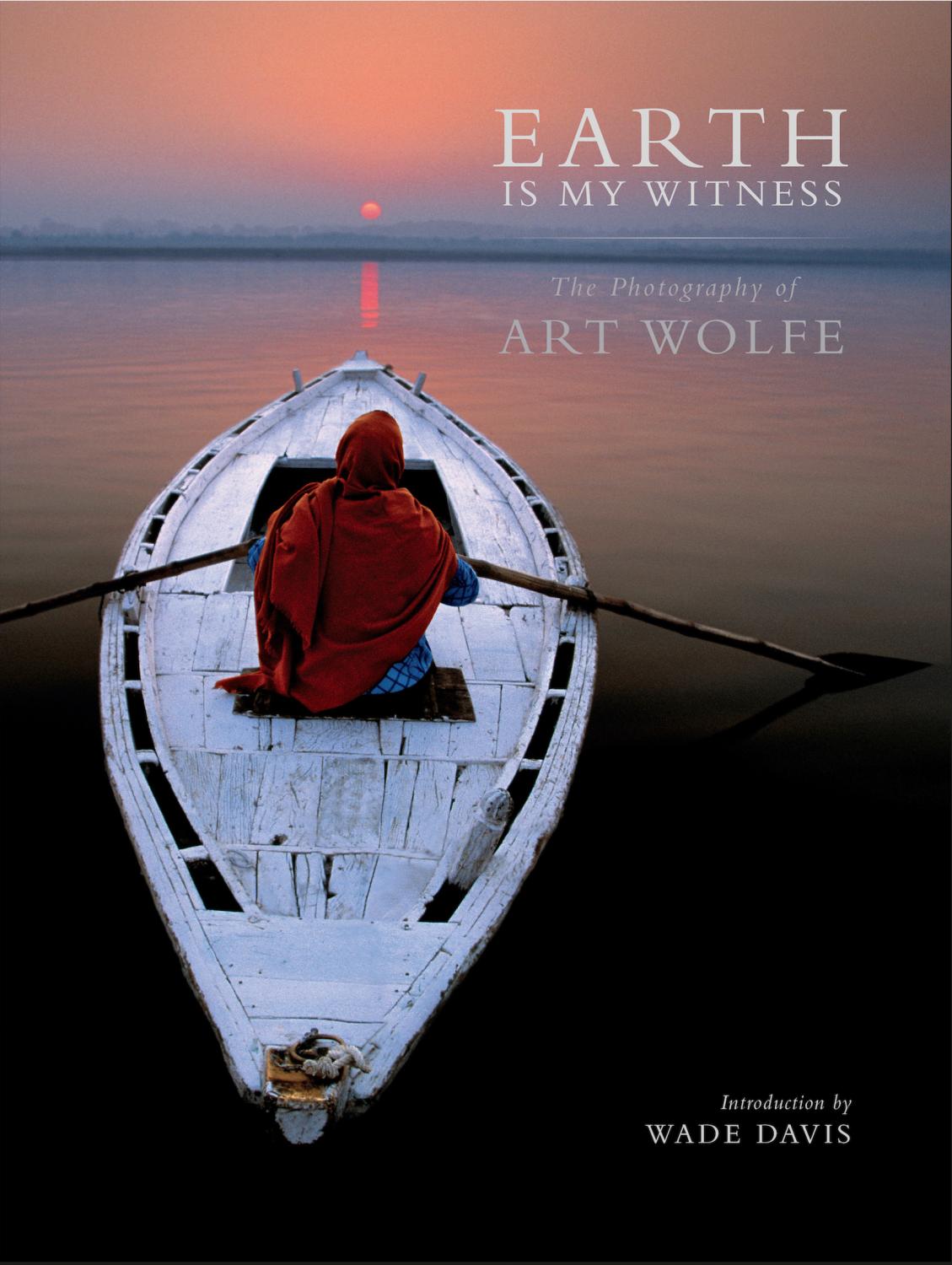

Art Wolfe's book Earth Is My Witness is out now, containing 40 years of expeditionary photography, including landscapes, wildlife and cultures on the edge of extinction. See https://artwolfe.com/collection/earth-is-my-witness/ for details or buy it HERE. Other recent books including Photographs From The Edge and Vanishing Act.

Art Wolfe’s TV series Travels From The Edge is also available on Amazon.

For more on Art Wolfe’s photography and upcoming projects, see artwolfe.com.

Photos in descending order: Art Wolfe and Southern Elephant Seal, South Georgia Island; Rainstorm over canyonlands, Moab, Utah by Art Wolfe; King Penguins, South Georgia Island by Art Wolfe; Yanomamo girl with blue-headed parrot, Parima Tapirapeco National Park, Venezuela by Art Wolfe; Art Wolfe gives caimans their close-up in Brazil's Pantanal while filming for television series Art Wolfe's Travels to the Edge.